Earlier this year I picked up the short and sweet “The Language Of The Corpse” by Cody Dickerson. I didn’t really want to write a book review as such with this, as much as I wanted to explore some of the themes and ideas within the book. While it focuses on the ritualistic understanding of death within ancient Germanic religions, this is not merely a study of these death rituals. It’s an exploration of the liminal space between life and death and our quest to find understanding in it. Dickerson’s work resonates deeply, offering a scholarly and visceral understanding of how humanity confronts and interprets its own mortality. His framework provides a valuable lens through which to analyze not only the funerary practices but also the human understanding of death and dying.

The central idea here, that the corpse itself becomes a text to be read and interpreted, is compelling to say the least. He meticulously details how societies and cultures through time have imbued the deceased with meaning, transforming the physical remains into a symbolic language. This “language” speaks volumes about a culture’s beliefs, fears, and hopes regarding the afterlife. This concept of the corpse as a communicative entity is not unfamiliar to those who explore any artistic expressions dealing with mortality. Ideas such as seances (in the broad sense of the term), divination and necromancy, all serve as an attempt to convene with the deceased. Numerous cultures around the world have all souls days or celebrations of the dead. Japanese Buddhism has the 3 day Obon Festival, where patrons honour the spirits of their deceased ancestors. Many artistic forms of this understanding frequently grapple with death, decay, and the transience of existence, often employing visceral descriptions of corpses and the processes of decomposition to come to terms with the process. Dickerson’s work here offers a theoretical framework for understanding this fascination with the afterlife and the questions that death itself forces us to ask.

Dickerson’s “The Language of the Corpse” offers more than just a description of funerary customs; it’s an insightful journey into the ancient Germanic psyche, where death was not necessarily a full stop but rather a transition into a different state of being, one that retained a powerful connection to the world of the living. For them, the deceased weren’t simply relegated to the past, fading from memory. Instead, the corpse was believed to pulse with a latent energy, a tangible link to the spiritual fabric of existence, radiating magical and spiritual power that held both promise and peril. His nuanced analysis of surviving folklore, the often-cryptic details within ritualistic practices, and the careful interpretation of historical fragments paints a compelling picture of societies that viewed death as a significant transformation, one that imbued the physical remains with a unique kind of agency. These societies imbued their dead with deep significance, seeing them as potential sources of wisdom, conduits to the otherworld, and even active participants in the affairs of the living. Consequently, the corpse was viewed as inherently powerful, a conduit for mystical forces that shaped their understanding of the cosmos, their relationship with the divine, and their own mortality. These lifeless remains, therefore, weren’t merely organic matter undergoing decomposition; they were charged with unseen energies, pathways through which influence could flow between the realms of the living and the dead. This fundamental understanding permeated their culture, deeply influencing their art, their social structures, and their spiritual beliefs.

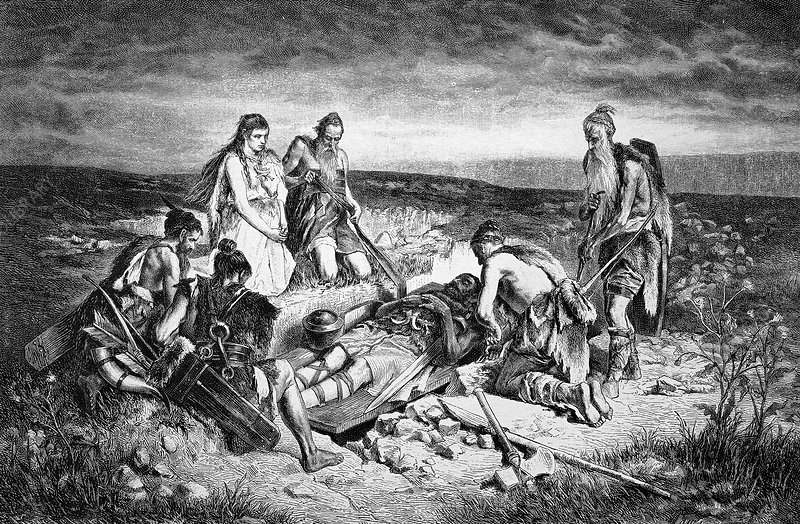

This powerful understanding of the corpse wasn’t confined to the realm of myth and legend; it actively manifested in the practicalities of their daily existence, shaping how they interacted with the world around them and sought to influence their destinies. Rituals surrounding death and burial were elaborate and imbued with deep symbolic meaning, reflecting this profound connection to the departed. The practice of magic, often intertwined with appeals to ancestral spirits or the utilization of physical remnants of the deceased, further underscores this relationship. Even the very structure of their society, with its emphasis on lineage and the honoring of ancestors, reflected the enduring influence of the dead. Dickerson’s meticulous examination of folk charms, often incorporating elements believed to retain the essence or power of the deceased, and the conscious construction of burial customs, designed to ensure the continued well-being of both the living and the dead, reveals the depth of this integration. The deceased were not just figures of the past to be mourned; they were active participants in the present, their influence sought for protection, guidance, and even the manipulation of fortune. Furthermore, the book expertly explores the often-indistinct boundaries between magic and religious practice in their treatment of the dead, highlighting the complex interplay of reverence, fear, and a desire to harness the power associated with the transition of death. Corpses, or specific parts thereof, were central to various sorcerous practices, believed to hold potent magical properties. The pervasive belief that the dead could actively impact the lives of the living, either through direct intervention or as a source of magical energy, underscores the complex emotional landscape surrounding death in these societies. We see this vividly in the careful selection and application of specific body parts in charms intended for healing, protection, or even harm, and in the deliberate design and placement of burial mounds, often seen as dwelling places for ancestral spirits and points of connection between the worlds.

Reading Dickerson’s work sparked a thought: The magic and mysticism aside, we can see the importance in the performative aspect of death rituals and their crucial role in accepting loss. With “The Language Of The Corpse” we can start to alter our understanding of funerals and other ceremonies. We can now see them not just as somber reflections, but instead, they are carefully constructed and orchestrated performances. These rituals serve vital functions: managing grief’s intensity, reinforcing the social fabric frayed by loss, and ultimately, attempting to make sense of the senseless. Providing a structured framework for expressing and processing profound sorrow is a key element. Through shared mourning and symbolic actions, such as specific prayers or the gentle placement of flowers, overwhelming emotions find a channel. Furthermore, the gathering of family and community strengthens social bonds, offering both practical and emotional support. This collective presence also solidifies the deceased’s enduring place within the community. Consider the laying of flowers, the intimate act of bringing the corpse into the home, or a designated period of mourning – these are all integral elements. They contribute to a ritualistic space, a sanctuary for individuals navigating the difficult terrain of loss.

This performative element finds a compelling parallel in the theatricality inherent in art forms grappling with death. If we first think of a shaman sitting at the burial mound, channelling his thoughts to that of the corpses that surround him. He aims for that altered state of consciousness to begin his reception of the signals the dead are sending. With that in mind, we can see the similarities in some musical performances. The use of costume, the elaborate and dramatic stage presentations, even the very architecture of vocal structures and styles – they conjure a liminal zone. Somewhere that is between the living and the dead. In this space, the boundaries between life and death, reality and myth, begin to blur.

Art in this context can be viewed as a contemporary evolution of more ancient ritualistic expression. Dickerson’s exploration of death’s rich symbolism resonates deeply with the esoteric themes often pulsing beneath the surface of these artistic explorations of the afterlife. From ancient symbols of rebirth and transformation, like the mythical phoenix or the enduring Ankh, to the starker imagery of decay and dissolution, the language of the corpse is steeped in occult significance. Artists frequently draw upon this potent symbolism, weaving it into the fabric of their creations. As Dickerson elucidates, by grasping the historical and cultural context of these symbols, our appreciation for the artistic choices made deepens considerably.

Attempting a conventional book review for “The Language Of The Corpse” felt unwarranted, this isn’t a lengthy book but the content opens up a huge conversation. The richness of Dickinson’s investigation excels with his ability to unpack complex ideas without resorting to lengthy passages. Instead he draws the reader in and invites us to instigate a broader discussion that resonates with our own anxieties and curiosities about death. This is a genuinely captivating and intellectually stimulating dive into ancient rituals and practices, and I wholeheartedly recommend it to anyone intrigued by the historical threads that connect us to our ancestors’ understanding of mortality. My aim here has been to offer a taste of the profound connections Dickinson draws, hoping to encourage your own initial steps in examining these ancient rituals and, perhaps more importantly, in reconsidering the lenses through which we view death itself.

– Zero

Leave a comment