Mithras sacrificing the Bull (100-200 AD) from the Borghese collection purchased in 1807 by the Louvre, photo by Serge Ottaviani.

Mithraism was pretty big between the 2nd to 4th century CE in Rome. However, despite the known existence of hundreds of Mithraea within the ancient city, only two Mithraic burial inscriptions have ever been discovered. Leading us to the question, where are the rest of the Mithraic graves?

Abstract

There is plenty of evidence to document the Cult of Mithras’ existence in the 4th century was widespread across the Roman Empire (Griffith, 1993; Sauer, 2012), however we have only found two distinctly Mithraic burial inscriptions.

This article looks to explore where the bodies might be by way of examining burial traditions in the city of Rome around the time of Mithras’ prominence and looks to discover why there are only two Mithraic inscriptions despite the presence of hundreds of Mithraea in Rome itself around the same time.

Introduction

By the mid 4th century scholars estimate there could have been as many as 250 active Mithraea, and possibly as many as 15’000 Mithraists within the city Rome. (Bjørnebye, 2007) This means Mithraism was not a small club, imagine 250 McDonalds in your city – there must have been one on every corner.

However, despite having 1700 years of archaeology enthusiasts digging around Ancient Rome we have only found two clearly Mithraic tombs. So, the premise today is simple. I am asking, where are the remaining bodies?

Through the course of this essay, I will propose and expand upon these three possibilities I believe have all played a part in why so few Mithraic resting places have been discovered:

Possibility 1: Roman burials were not always segregated by religion.

Possibility 2: Mithraism was a mystery cult whose graves were not easily identifiable.

Possibility 3: They weren’t buried.

Mithraism: Where Are The Bodies? (An Exploration Into Mithraic Burial Practices, by D.)

To date, only two Mithraic graves have been identified in the city of Rome: the arcosolium of Caricus, a priest of Mithras, and the shared tomb of Aurelius Faustinianus and his brother, Aurelius Castricius, who were also Mithraic priests. Both resting places are located in the Hypogeum of Vibia along the Via Appia. (Simón, 2018).

The Hypogeum of Vibia itself is a private cemetery consisting of seven different hypogaea, all of which were built separately but interconnected at some later point in history as the area was excavated to build additional burial spaces.

To save you a Google, a hypogeum is an underground chamber used for burials or religious purposes, and an arcosolium is a type of memorial space consisting of an arched recess carved into a wall, typically used to house small items or the remains of the individual.

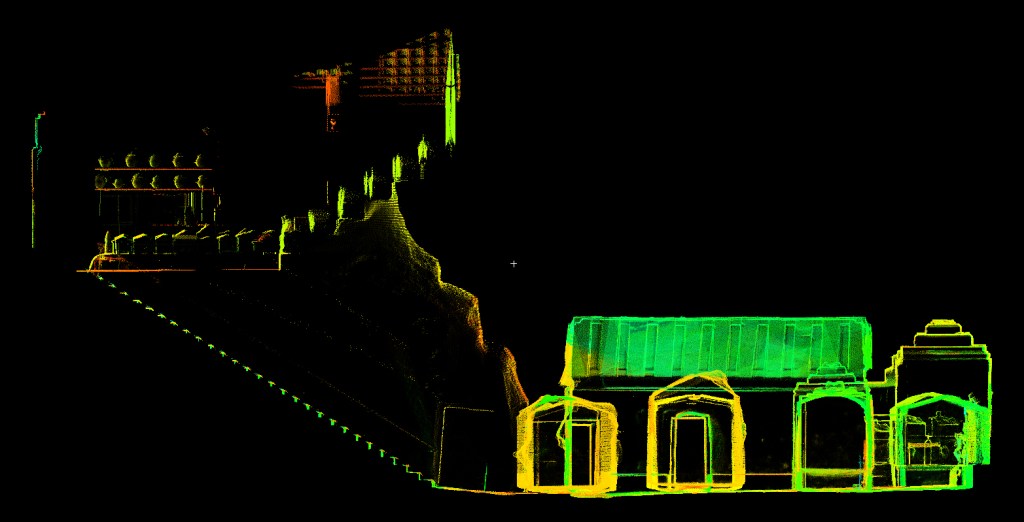

An example of a hypogeum: 3D laser scan profile of the Hypogeum of the Volumnus family, scan by CyArk.

The Mithraic identification comes down to the inscriptions, but as we’ll discover there is also some interesting artwork in the same hypogea whose origins are unclear.

But let’s start with what we know to be Mithraic:

As Vittoria Canciani notes in their 2022 dissertation, the first inscription (a marble slab measuring 38 x 79 cm) was discovered in 1952 in the Catacomb of Vibia and dates to the 4th century CE. It is currently preserved in situ within the arcosolium of SS. Peter and Marcellinus. It’s inscription states:

D(iis) M(anibus). Sanctae adquae peraenni bone memoriae viris Aurelii[s] Faustiniano patri, et Castricio fratri, sacerdotibus Dei Solis Invicti Mithrae, eredes aeorum prosecuti sunt, e[t] b(onae) m(emoriae) Clodia Celerianae matri f(ecerunt).

Which roughly translates to, “To the spirits of the dead (‘to the Manes’). For the holy and eternal good memory of Aurelius Faustinianus, father, and of Aurelius Castricius, brother, priests of the god Sol unconquered Mithras, and also for the good memory of Clodia Celeriana, mother. Their heirs follow.”

The second inscription is a painted funerary inscription discovered in 1852 within the Catacomb of Vibia, dating to the 3rd century CE. It is currently preserved in situ, within gallery V3 of the same catacomb in Rome. (Canciani, 2022.) The second inscription states:

D(is) M(anibus) / M(arcus) Aur[—] s(acerdos) d(ei) S(olis) I(nvicti) M(ithrae) / qui bas[i]a [v]oluptatem iocum alumnis suis dedit / ut locu[—]e et natis suis / [—]en locus carici / [—]so proles.

Approximately translating to, “To the spirits of the dead (‘to the Manes’) / Marcus Aurelius …, priest of the god Sol unconquered Mithras, who gave kiss, love, and tenderness to his pupils, for … for himself, his wife, and his children, … place of … offspring.”

Dining scene with inscription SABINA MISCE in arcosolium 75, the catacomb of SS. Peter and Marcellinus, c. 320-360 AD. Adapted from: Ingle, 2019, who cites Giuliani, 2015, in their article.

And what about the painting?

As Gabriela Ingle from the University of Edinburgh notes in their 2019 article for Studies In Ancient Art And Civilization, there is good reason to suspect that the image painted into the arcosolium at the catacomb of SS. Peter and Marcellinus was not Christian.

As the author notes, […]”The lunette of arcosolium is decorated with a dining scene supplemented with the inscription SABINA MISCE (‘Sabina, mix!’) (Pl. 3: 1-2), which closely resembles the inscriptions of Agape and Irene found in seven neighbouring tombs. For this reason, the arcosolium has been commonly interpreted as Christian and not much attention has been paid to the rest of the tomb’s decoration (e.g. Jastrzębowska 1979, 22; Dunbabin 2003, 178). However, the scene with Sabina is not unique because of its unusual inscription but because a) it is not supplemented by any image that could potentially reflect the Christian faith (i.e. a biblical or miracle scene or even an orant), b) the dining scene itself differs from the convivial representations found in the neighbouring cubicula, and c) an additional dining scene is represented on the wall above the arcosolium.”

Although it would be fascinating if it was a Mithraic hypogaea, rather than a more generic ‘Pagan’ burial site, the point of this article was not to speculate about the Arcosolium of the Mysteries itself. The point of this article was to speculate on why so few Mithraic burials have ever been found. (Meaning, if you’d like to learn more about the painting directly, please refer to the author’s original work.)

I present three possibilities I believe to be working in tandem as the most likely reasons for why so few Mithraic graves have been found.

Possibility 1

In ancient Rome, burials were not always organised according to religious affiliation, which means that individuals affiliated with the cult of Mithras may be interred across a wide range of burial sites without any overt indication of their religious identity. Instead, burial practices were often shaped by factors such as social status, occupation, family ties, or membership in collegia (such as associations or guilds). A clear example of occupationally based burial organisation can be seen in the collegium of cooks at the Catacomb of Pretextatus, where members of the same trade were buried together, regardless of their personal religious beliefs (Borg, 2013). Additionally, burial contexts in Rome also reveal ethnic and cultural diversity, with sites like the Coemeterium Iordanorum on the Via Salaria displaying evidence of mixed-race and multicultural interments (Borg, 2013). These examples suggest that the absence of explicitly Mithraic graves may not indicate the absence of Mithraic adherents but rather reflect the broader Roman practice of integrating individuals of diverse beliefs into communal or occupational burial grounds, where religious identity was not always prominently marked.

Possibility 2

Mithraism was a mystery cult with its rituals, beliefs, and membership being deliberately kept hidden, a secrecy that may have extended into death. As previously mentioned, the graves of Mithraic adherents are difficult to identify, since they do not appear to include distinctive symbols or funerary customs that would clearly differentiate them from other Roman burials. This has been further masked by a long‑standing tendency to interpret catacomb material as Christian by default, dating back to their rediscovery in the sixteenth century (Ingle, 2019). Unlike Christianity, which developed a recognisable funerary iconography, Mithraism seems to have lacked visible or consistent burial markers, making its followers archaeologically invisible in most cases. The few Mithraic graves that have been identified (such as those of high-ranking priests) may be exceptions rather than the norm. Additionally, the hostile attitude of early Christians toward Pagan cults may have contributed to the deliberate erasure or defacement of Mithraic symbols, especially as Christianity gained dominance in the later Roman Empire. The vandalism by later Christians, combined with the cult’s secrecy and possible lack of formalised funerary practices, only further complicates efforts to trace Mithraic presence through the archaeological record of Roman burials.

Possibility 3

Another important factor to consider is that not all Roman dead were buried in underground tombs; in fact, cremation was the dominant funerary practice for much of the Roman Republic and early Empire (Noy, 2000). Cremation remained a widespread and culturally normative method of disposing of the dead well into the Imperial period. It is therefore entirely plausible that many followers of Mithras were cremated, leaving behind little to no surviving archaeological evidence. This would be especially so if their ashes were then interred in modest urns or scattered, rather than entombed in elaborate structures. The few inscriptions associated with Mithraic priests that have been found may not represent typical burial practices of the broader Mithraic community, but rather serve as commemorative or venerated sites, possibly erected due to the individual’s elevated status within the cult.

Future Research

This following paragraph is speculative conjecture, but I question is it unreasonable to imagine a religion fascinated by fire may have preferred cremation to burial? I also wonder, is it also unreasonable that a cult surrounded in mystery during life may have also preferred anonymity in death? These are questions I cannot concretely answer, but they are the questions I am left with that I hope can be answered more definitively as more Mithraic artifacts emerge over time.

In Conclusion

The near-total absence of clearly identifiable Mithraic burials in Rome remains a striking contrast to the widespread presence of Mithraea across the city in the 2nd to 4th centuries CE. This article has outlined three plausible explanations: that Mithraic followers were buried in mixed or occupational cemeteries without religious distinction; that the secrecy of the mystery cult, combined with later Christian hostility, obscured their funerary traces; and that many adherents may have been cremated, leaving little archaeological evidence behind. Taken together, these factors suggest that the missing Mithraic dead are not truly missing but rather hidden within the broader fabric of Roman funerary practice, and, if surviving, potentially misidentified as belonging to the affiliations of those buried beside them rather than being identified as uniquely Mithraic.

BOSTKTB,

HTBLOF.

-D

Primary Citations:

Gabriela Ingle – A FOURTH CENTURY TOMB OF THE FOLLOWERS OF MITHRAS FROM THE CATACOMB OF SS. PETER AND MARCELLINUS IN ROME (from Studies in Ancient Art and Civilization, vol. 23, 2019)

David Noy – ‘HALF-BURNT ON AN EMERGENCY PYRE’: ROMAN CREMATIONS WHICH WENT WRONG (from Greece & Rome, Vol. 47, No. 2, October 2000)

Francisco M. Simón – A PLACE WITH SHARED MEANINGS: MITHRAS, SABAZIUS, AND CHRISTIANITY IN THE “TOMB OF VIBIA” (from Acta Ant. Hung. 58, 2018)

Alison B. Griffith – THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE FOR MITHRAISM IN IMPERIAL ROME (1993)

Jonas Bjørnebye – THE CULT OF MITHRAS IN FOURTH CENTURY ROME (from Dissertation for PhD, 2007, via Mithraeum.eu)

Vittoria Canciani – ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE OF THE CULT OF MITHRAS IN ANCIENT ITALY (from Dissertation, 2022 via Università di Verona)

Secondary Citations:

Barbara E. Borg – CRISIS AND AMBITION: TOMBS AND BURIAL CUSTOMS IN THIRD-CENTURY CE ROME (2013)

Eberhard Sauer – MITHRAS AND MITHRAISM (from The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, 2012)

Raffaella Giuliani – THE CATACOMBS OF SS. MARCELLINO E PIETRO (from The Catacombs of Rome and Italy 11, 2015)

Leave a comment