The fourteenth century stands as a stark testament to human fragility, an epoch defined by a relentless convergence of calamities that shattered the very foundations of medieval Europe. This was not just a period of hardship, but a crucible of unprecedented devastation, where the abstract terrors of widespread destruction materialized into tangible, all-consuming realities. Widespread conflict, severe famine, and rampant disease, each a formidable force in its own right, coalesced into an overwhelming storm, culminating in the Black Death, a pandemic of such scale and ferocity that it irrevocably altered the course of human history. Here, we’re going to take a look at the intricate interplay of these destructive forces, examining the origins and gradual westward creep of the plague, alongside the pre-existing conditions of warfare and starvation that rendered Europe a fertile ground for its ultimate, cataclysmic harvest.

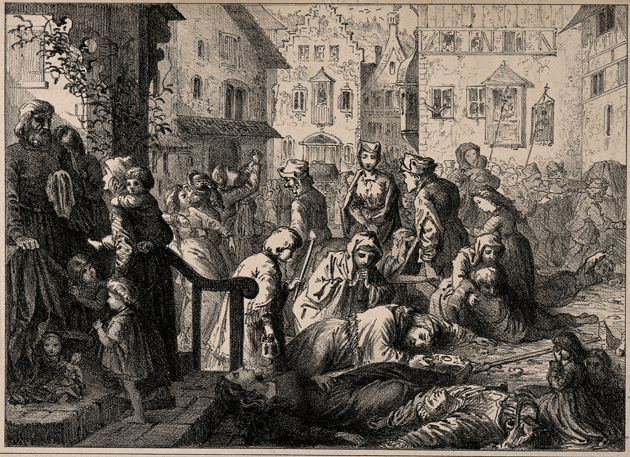

Illustration of the burial of plague victims – Pierre Du Tielt circa 1350

The genesis of the Black Death, the most lethal pandemic in recorded history, was not a sudden, inexplicable curse, but the culmination of a complex biological process rooted in the ancient, often unforgiving landscapes of Central Asia. The primary causative agent, the bacterium Yersinia pestis, had long existed naturally within animal populations, among various species of wild rodents in the grasslands and mountain regions of Asia. Specifically, modern genetic and archaeological research has pinpointed the Tien Shan mountain range, particularly areas around Lake Issyk Kul in present-day Kyrgyzstan, as a likely geographical origin for the specific strain responsible for this fourteenth-century pandemic.

Within these natural breeding grounds, Yersinia pestis maintained a delicate, albeit lethal, equilibrium with its primary hosts, typically marmots, gerbils, and other burrowing rodents. The bacterium cycles between these rodents and their parasitic fleas, primarily the Oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis). When a flea feeds on an infected rodent, the bacteria multiply in its foregut, forming a dense biofilm that obstructs the proventriculus. This blockage starves the flea, driving it into a frenzied hunger, compelling it to bite repeatedly. As it attempts to feed, the flea regurgitates blood and a concentrated inoculum of bacteria into the bite wound, thereby transmitting the pathogen to a new host. This intricate biological mechanism, perfected over millennia, ensured the persistence of the plague within its natural reservoirs.

Evidence suggests that localized outbreaks, or epizootics, were occurring across Central Asia for decades, if not centuries, prior to the European pandemic. Tombstone inscriptions from the Kara-Djigach and Burana sites near Lake Issyk Kul, dating to 1338 and 1339 Common Era, explicitly mention deaths from “pestilence,” providing at least some archaeological proof of a significant, localized human epidemic that predated the Black Death’s arrival in Europe. This indicates that the Yersinia pestis strain had already achieved a high degree of virulence and transmissibility within human populations in its native environment, slowly gathering its strength before its explosive westward expansion. The initial spread was not a sudden eruption but a gradual, insidious creep, driven by the persistent, albeit often localized, interactions between humans and infected rodent populations along the arteries of trade.

Die Pest In Winterhur im Marz 1328 (1860) by August Corrodi

While the biological engine of the plague slowly churned in the East, Europe was already being ravaged by widespread conflict, a force that systematically dismantled its social structures and weakened its populace. The fourteenth century was an era defined by incessant warfare, both large-scale dynastic struggles and localized feudal skirmishes. Foremost among these was the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453), a protracted and brutal conflict between England and France. This was not a singular war, but a series of devastating campaigns, sieges and mounted raids that laid waste to thousands of acres of the French countryside.

The impact of this prolonged warfare extended far beyond direct combat casualties. Armies, often composed of mercenaries and professional soldiers, engaged in systematic destruction of agricultural lands, burning crops, razing villages, and disrupting the delicate balance of medieval agrarian economies. This deliberate devastation led to localized famines and chronic food insecurity, further weakening the general population. The constant movement of large bodies of troops, often numbering in the tens of thousands, across vast territories created ideal conditions for the dissemination of various pathogens, including dysentery, typhus, and other horrific diseases. Soldiers, living in close quarters with abysmal sanitation, served as mobile reservoirs and vectors for these infections, spreading them to the civilian populations they encountered or plundered.

Siege warfare, a hallmark of the Hundred Years’ War, was particularly conducive to disease transmission. Besieged populations, trapped within walls, faced acute shortages of food and potable water, leading to widespread malnutrition and a heightened susceptibility to illness. The besieging armies outside the walls also suffered immensely from exposure, poor hygiene, and the inevitable spread of contagion within their own ranks. The infamous siege of Kaffa in 1347, a Genoese trading outpost in Crimea, serves as a grim example of warfare’s role in the plague’s spread. While the dramatic narrative of Mongol forces catapulting plague-infected corpses over the city walls is often cited, the more plausible scenario involves the introduction of infected rats and fleas into the closed city, and subsequently onto the fleeing Genoese ships. This act, whether deliberate or incidental, highlights how military movements and their associated disruptions could inadvertently act as super-spreaders for as it stood, a fairly dormant epidemic.

Beyond the Hundred Years’ War and the Siege of Kaffa, numerous regional conflicts across Europe—from the Scottish Wars of Independence to various internal dynastic struggles within the Holy Roman Empire and Italian city-states—further contributed to the pervasive instability. These conflicts disrupted trade routes, diverted resources, and maintained a state of chronic vulnerability across the continent. Similarly, in Asia, the vast Mongol Empire, while facilitating trade, also experienced periods of internal strife and military campaigns that could have contributed to the westward movement of the plague. The cumulative effect of this widespread, incessant warfare was a continent physically scarred, economically disrupted, and populated by a populace already weakened and less resilient to external shocks.

As the shadow of conflict continued its destructive work, famine had already reaped its own devastating harvest across Europe, leaving a populace profoundly weakened and susceptible. The early fourteenth century witnessed a series of severe climatic shifts, ushering in a period of colder, wetter weather that marked the onset of the Little Ice Age. This change in the climate across Europe had immediate and catastrophic consequences for medieval agriculture.

Plague (1898) by Arnold Bocklin. currently held in Kunstmuseum, Basel

The most acute manifestation of this climatic shift was the Great Famine of 1315-1317, though its effects lingered for several years thereafter. Unusually heavy and prolonged rainfall during crucial planting and harvesting seasons led to widespread crop failures across much of Northern Europe. The agricultural practices of the time, already operating close to their maximum capacity due to a burgeoning population and limited technological advancements, were utterly unprepared for such sustained adverse conditions.

The consequences were immediate and dire. Grain yields plummeted, leading to acute food shortages and hyperinflation of food prices. The price of wheat, for instance, in England increased by over 300 percent between 1314 and 1316. Livestock, deprived of fodder and succumbing to disease exacerbated by the wet conditions, died in vast numbers, further diminishing food supplies and economic stability. The poor, who constituted the overwhelming majority of the population, were hit hardest. Chronic malnutrition became endemic, leading to widespread starvation and this led to an increase in susceptibility to other diseases. Accounts from the period describe harrowing scenes of widespread starvation, with reports of desperate measures, including infanticide and even cannibalism, emerging from the most afflicted regions.

While precise mortality figures for the Great Famine are challenging to ascertain due to fragmented records, it is estimated that the famine alone claimed the lives of 10-15 percent of Europe’s population in some regions, with localized areas experiencing losses as high as 25 percent. For example, in England, the population is estimated to have declined by 5-10 percent during this period. Beyond direct mortality, the famine left a legacy of chronic ill-health, stunted growth, and weakened immune systems across the surviving population. Generations grew up undernourished, their bodies less capable of resisting infection. This pre-existing state of widespread malnutrition and compromised health was a critical, often overlooked, factor in the subsequent, unparalleled devastation wrought by the Black Death. A continent already physically and psychologically exhausted by decades of food insecurity and high mortality presented a perfectly primed host for the ultimate infection.

Into this landscape, already scarred by widespread conflict and hollowed out by famine, rode the force of utter pestilence, in its most brutal and efficient form: the Black Death. The plague’s arrival in Europe was not a sudden, isolated event, but the culmination of a gradual westward movement along established trade routes, amplified by the existing vulnerabilities.

The pivotal moment for Europe was the aforementioned siege of Kaffa in 1347. While the Mongols’ alleged use of plague-infected corpses is a dramatic (most probably fictitious) detail, the more significant epidemiological factor was the presence of infected rats and fleas within the city and, crucially, aboard the Genoese merchant ships that fled the port. These vessels, effectively veritable death ships, carried the plague directly into the heart of the Mediterranean trading network.

Plague Victims During the Siege of Leiden

The first documented landfall in Europe was in Messina, Sicily, in October 1347. The arrival was marked by immediate and horrifying mortality among the ships’ crews and the local population. From Messina, the plague spread with terrifying speed. Panicked refugees fleeing infected areas inadvertently carried the disease to new towns and cities. Merchant ships, continuing their trade routes, became conduits of contagion, infecting port after port. By January 1348, it had reached Marseille, France, and quickly spread inland along rivers and roads. By mid-1348, it had engulfed major cities in Italy, France, and the Iberian Peninsula. By August 1348, it reached England, landing at Melcombe Regis (modern-day Weymouth), Dorset, and by 1349, it had swept across Scandinavia, parts of Eastern Europe, and the British Isles.

The sheer speed of its dissemination, faster than could be accounted for by rat and flea migration alone, strongly suggests a significant role for the pneumonic form of the plague. This highly contagious variant, transmitted directly from person to person via respiratory droplets, allowed the disease to leapfrog vast distances and decimate populations in a manner distinct from purely bubonic outbreaks. Every cough became a potential death sentence, every breath a murder weapon. This relentless, inexorable march across a continent already weakened by warfare and famine created a perfect storm of mortality, a biological catastrophe amplified by pre-existing societal vulnerabilities.

The fourteenth century was not just a period of isolated misfortunes; it was a unique historical crucible where the distinct yet interconnected forces of widespread conflict, severe famine, and rampant disease converged to unleash an unprecedented wave of death. The deep origins of Yersinia pestis in Central Asia, its slow but persistent spread along trade routes, and its eventual explosive arrival in Europe were not isolated phenomena. They were inextricably linked to a continent already reeling from decades of relentless warfare and devastating food shortages.

The Hundred Years’ War and other regional conflicts had destabilized societies, disrupted agriculture, and created mobile vectors for disease in the form of armies. The Great Famine, a consequence of climatic shifts, had left millions malnourished, their immune systems compromised, their resilience shattered. And it was into this landscape of physical and psychological exhaustion, the Black Death arrived, a biological weapon of unparalleled efficiency, finding a perfectly primed host population.

The confluence of these three distinct yet synergistic events resulted in a scale of death previously unimaginable. Widespread conflict had laid waste to the land, famine had starved its inhabitants, and pestilence delivered the final, devastating blow, ensuring that the ultimate harvest of death would be the most profound and transformative event in European history. This period serves as a chilling reminder of humanity’s inherent fragility when confronted by the relentless, converging forces of nature and its own destructive tendencies, leaving an indelible scar on the collective memory and fundamentally reshaping the trajectory of Western civilization.

– Zero.

Leave a comment